Naoya Hida & Co. is an independent watch atelier in Tokyo producing a small number of classically-inspired watches in annual batches. As discussed in my recent blog post, Naoya Hida has introduced three models since 2019. Each model uses a customized movement based on the ETA 7750 automatic chronograph ebauche, a surprising choice because Hida’s watches are neither automatic nor chronographs! This being Grail Watch, I spent a good amount of time digging into the Hida calibres and am documenting them here on Grail Watch Reference.

The NH Cal. 30 Family

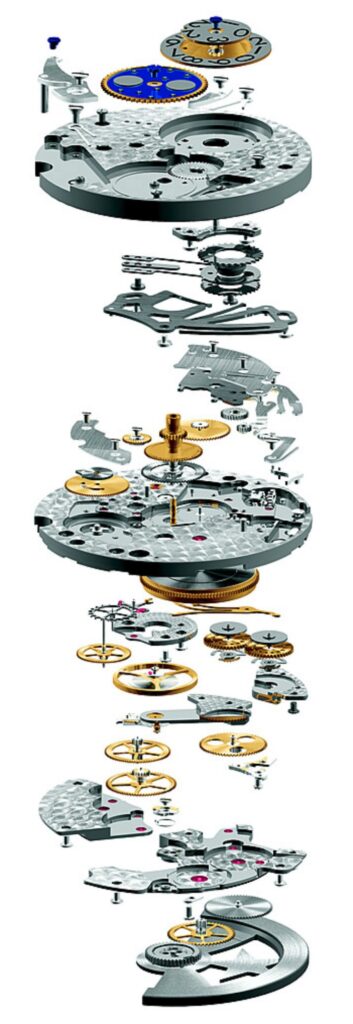

All three Hida movements to date have a similar appearance, and all are based on the 7750 ebauche, wheel train, barrel, balance, and escapement. The small seconds and moon phase movements likely share the same balance bridge and plate, and both feature 18 jewels.

The central seconds hand on Cal. 3020CS is driven using a rear-mounted wheel, requiring a secondary plate at the center. It also features four extra jewels, for a total of 22.

Cal. 3021LU, used in the Type 3, uses the moon phase mechanism from ETA’s Cal. 7751 but omits a seconds display entirely. Like Cal. 7751, the moon phase indicator is adjusted with the crown in position 2.

Grail Watch Commentary

The following is taken from my article, “The Neo-Classical Watches of Naoya Hida“

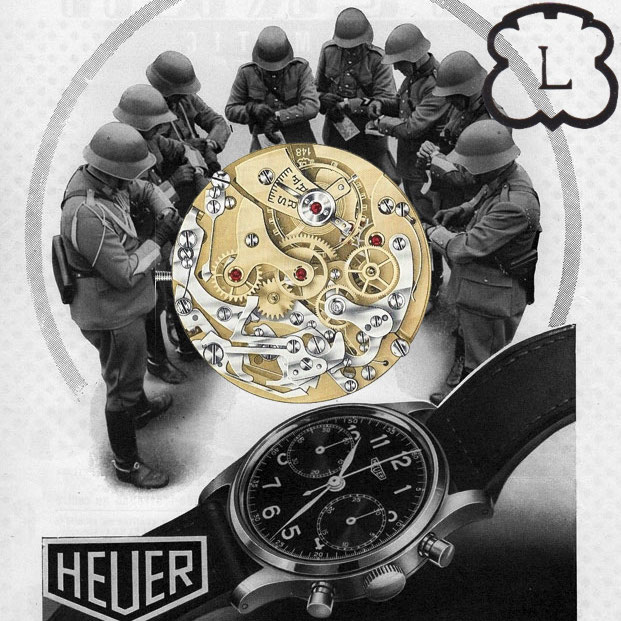

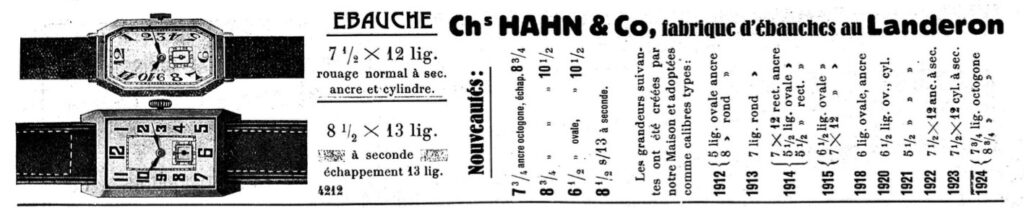

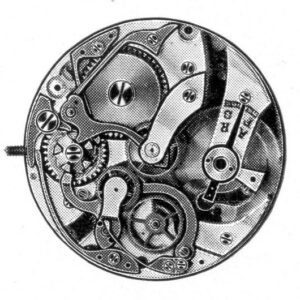

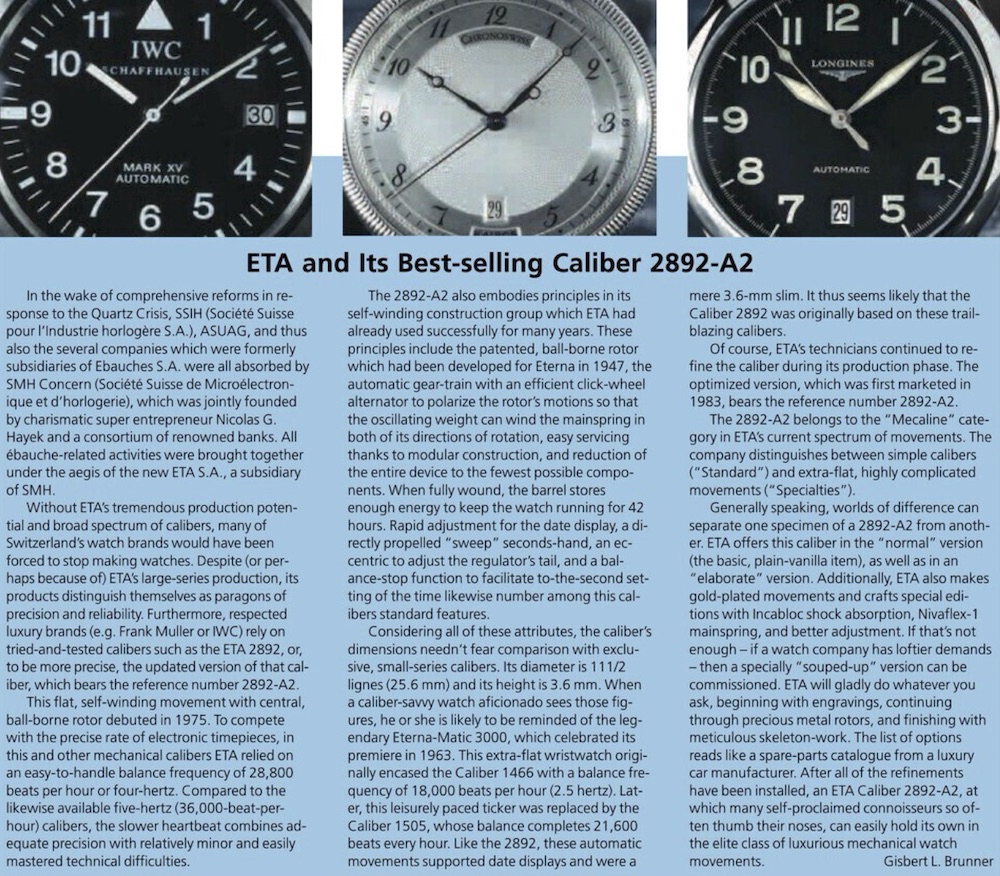

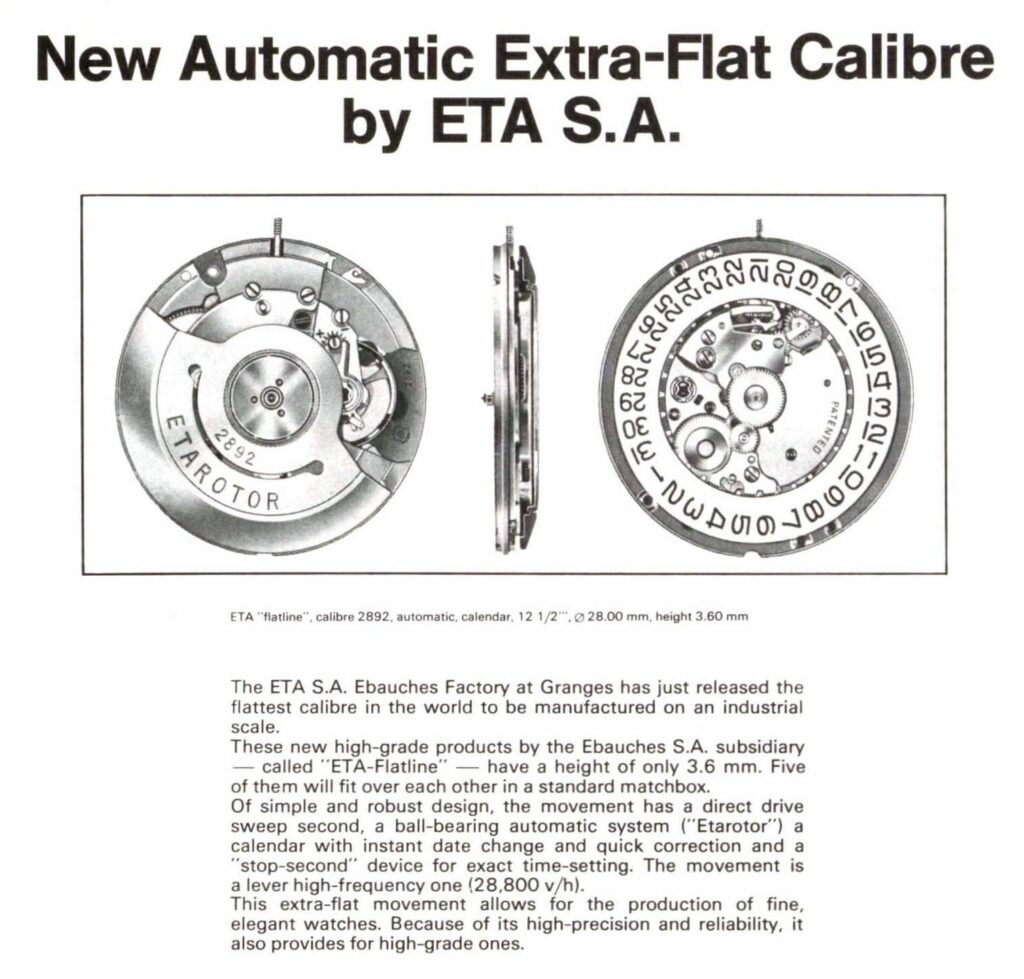

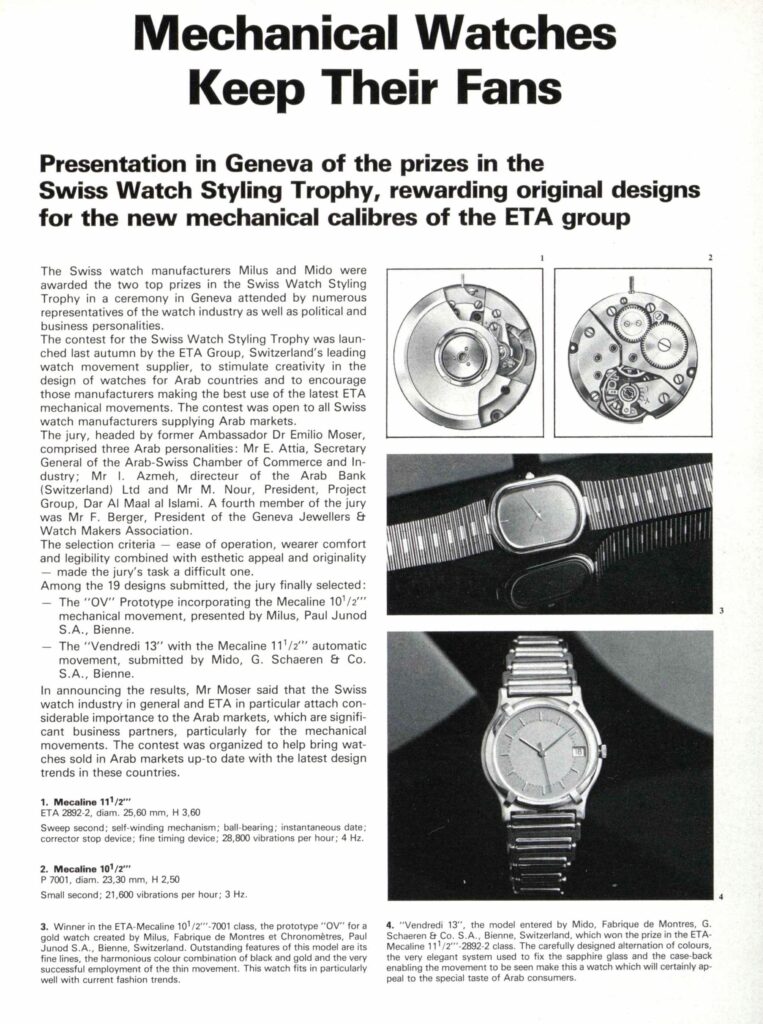

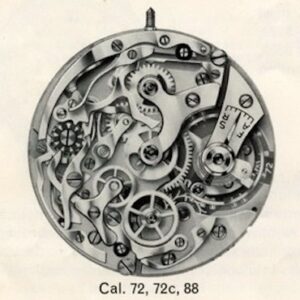

All of Naoya Hida’s watches produced to date rely on movements based on the classic ETA 7750. Designed by the legendary Edmond Capt, this movement originated at Valjoux and was released in 1974. It was an influential and popular automatic chronograph and served as one of the primary engines of the resurgence of mechanical watchmaking in the 1980s. Indeed, look inside the legendary IWC Da Vinci and later grand complications and you’ll find Capt’s 7750 ebauche!

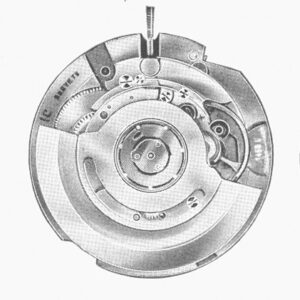

Although it might seem odd that Hida would use an automatic chronograph ebauche for his simple hand-winding watches, it is in keeping with watchmaking tradition. The 7750 provides a reliable and easily available base and this will ease concerns about serviceability in the future. And many other movements use the Cal. 7750 wheel train, including ETA’s own Valgranges family and quite a few column wheel chronographs.

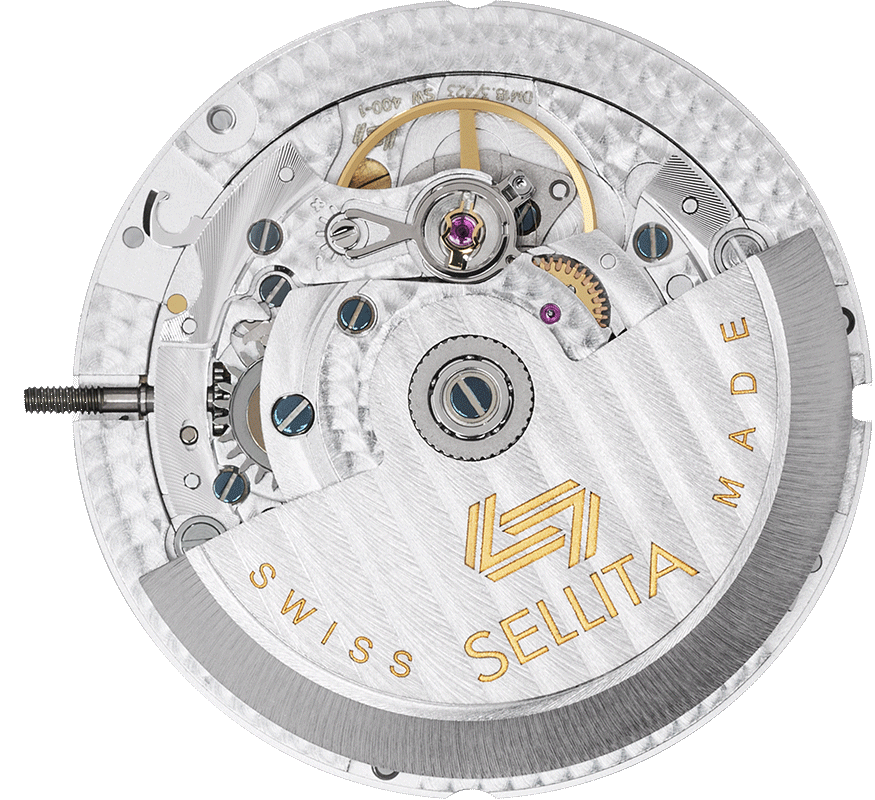

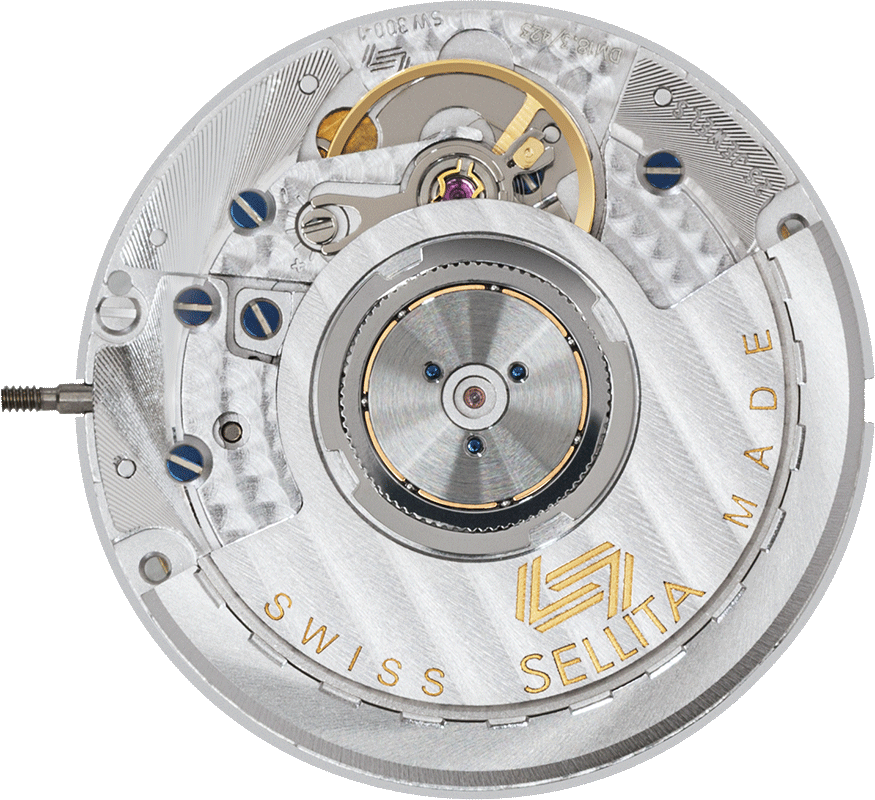

The use of the 7750 ebauche is popular among makers of fine independent watches as well. The Hida movement is especially reminiscent of the Habring² Felix Cal. A11, which uses this base for their hand-winding time-only movement with a custom balance bridge and plate. But Habring also uses an in-house escapement and hairspring. Most other independent watchmakers use ETA and Sellita ebauches with varying levels of customization or finishing, though some have adopted more specialized movements, especially in this price range.

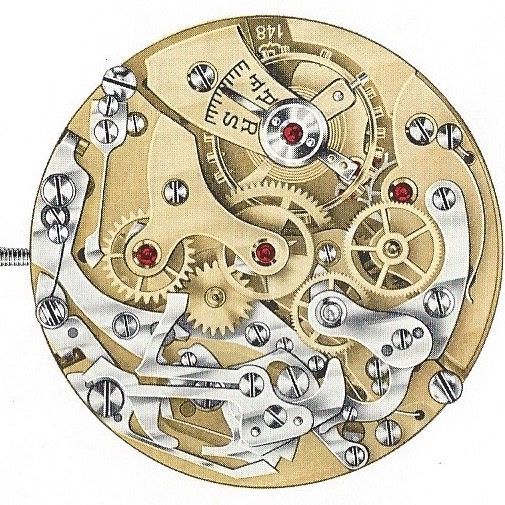

Hida obviously omits the automatic winding and chronograph components when his Cal. 30xx series movements are constructed, but there are many other changes besides. Notably, each movement is fitted with a Glashütte-style 3/4 plate, which sandwiches nearly the entire movement apart from the balance wheel and Hida-specific balance bridge. The plate does not use chatons, which traditionally made it easier to assemble 3/4 plate movements, but the chatons on most modern Glashütte movements aren’t functional so this is not that odd.

All Hida movements use a proprietary click mechanism to improve the feel when winding by hand. Good winding feel is curiously absent from many high-end watches, so I applaud this change. The wheel train, assortment (balance and escapement), and mainspring are held over from the 7750, as are the springs and shock absorbers. Thus, the movement operates at 4 Hz (28,800 A/h) and has a power reserve of around 45 hours. Without the chronograph components, Hida’s movements have 18 or 22 jewels.

The movement plate is decorated with a concentric pattern of overlapping spirals. Given the resources of the company, it is likely that this plate and the balance bridge are produced by an outside company, but it is nicely decorated, with engraved gold-filled lettering. The main plate still retains the ETA cloverleaf and “775x” stamps and does not appear to be re-worked or finished at all.

This is one key criticism that has been leveled against Hida’s watches: That the finishing of the ETA components is not up to his standards and thus de-values the entire watch. Given the widespread use of off-the-shelf timekeeping components, especially among independents, movement finishing is one element that often draws attention from critics. Indeed, one would hope that Hida and his staff could finish the ebauche to a standard that matches their bridge and plate at this price point. The same criticism can be leveled against some other independent watchmakers, but most are meticulous about finishing their movements.

On the other hand, it would not be fair to criticize Hida’s choice of the ETA 7750 ebauche. It is a well-respected and widely-used timekeeper, from IWC’s Il Destriero Scafusia to Omega’s Speedmaster Racing to most of the Habring² line. And nearly every member of the AHCI has worked on an ETA ebauche. Indeed, it will be easier to maintain and repair the ETA components than those from a more-exclusive maker.

Research Notes

There are not many photos of Hida’s movements available. The company has published one photo of each movement in their website specifications (the blue background images in the table above) as well as a “hero” shot of each movement on Instagram. But none of these reveals the dial side of the ebauche or many other details.

The ETA ebauche finishing is not up to the standards of the 3/4 plate and bridge in these photos, but this may not reflect the finishing of production watches. Because Hida’s watches do not include a display casebook, production movement finishing has not been revealed.

Hida has published specifications on the movements, including the thickness and jewel count of each. But there are no further details on the custom click mechanism or other modifications. Although it is apparent that Hida uses a simple ETACHRON with no index, this is not mentioned in any official source.