While working on my coverage of the Saint-Imier watchmaking industry, which leans heavily on chronographs, a few other names occupied my thoughts: Many people are aware of the classic Valjoux movements, and Universal, Lemania, and Venus are also respected. But there is much less coverage of Landeron, the factory of Charles Hahn that produced many high-end column wheel movements before introducing the world to cam switching. For this reason, I have recently added most of the classic Landeron chronograph movements to the Grail Watch Reference database.

Charles Hahn’s Factory in Le Landeron

Le Landeron is a small village on the western corner of Lake Bienne in the Canton of Neuchâtel. It is best known for its lovely medieval town center, surrounded by fields and vineyards. But Le Landeron was also home to industry, including the famous watch movement factory established by Charles Alfred and Aimé Auguste Hahn in 1873. This was located on the road to Neuveville along the railroad tracks a short distance from the historic town.

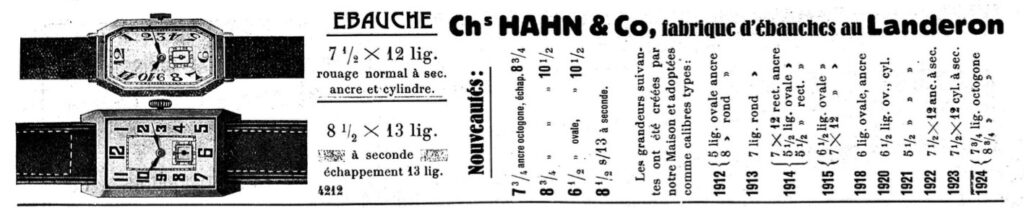

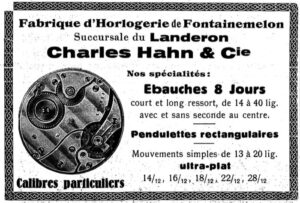

Hahn Frères et Cie. produced watches and watch movements in Le Landeron in the 1880s, winning medals and building a reputation for finely finished products. Their specialty was small movements and watches for women, many of which used cylinder escapements, but they also produced chronographs and 8-day clocks.

Image: Jelosil

As was typical at the time, the factory is exaggerated a bit in contemporary engravings, as is immediately obvious when viewing the factory today. The building remains in use by Jelosil, a manufacturer of quartz and UV lighting. But it thrived for decades, producing millions of watch movements.

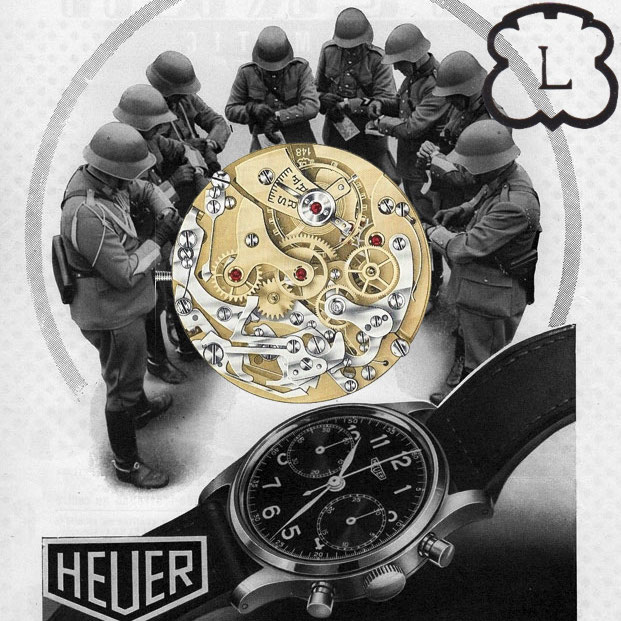

Charles Hahn’s factory merged with a similar ebauche factory in nearby Fontainemelon in 1925 and became a founding member of Ebauches SA the following year. The output of the factory shifted at this point to focus on chronographs, which were developed by Charles Hahn in association with Marcel Dèpraz in the Vallée de Joux. It was said that Hahn purchased the oscillating pinion patent of “Anatole Breitling” that year, but there are no contemporary references to this person, and this invention is more associated with Heuer not Breitling. Regardless, Hahn did produce column wheel chronograph movements at this time, and quickly became the primary supplier for Breitling, which was dominating the market for chronograph movements, as well as military and aviation.

But column wheel chronographs were expensive and difficult to produce, and military users in particular demanded something cheaper. In the 1930s, Charles Hahn and Marcel Dèpraz co-developed a novel new technique that used simple stamped plates to start, stop, and reset the hands of a chronograph movement. Their cam-switching technique would revolutionize the chronograph market, dramatically dropping the price of the technology and leading to a wave of new movements. After the patent was issued in 1939, over 3.5 million movements in the Landeron Cal. 48 family would be produced and sold by 1970. Venus soon followed Landeron with their own cam-switching chronograph movement, and this would be the basis for the famous Valjoux 7750 automatic chronograph in the 1970s.

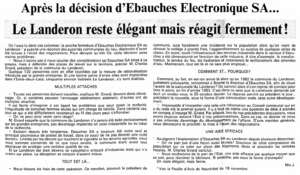

Landeron would innovate once again in the 1960s, introducing the first Swiss electric movement. Cal. 4750 used an electro-mechanical balance wheel powered by a battery, answering competitors from France, the United States, and Germany. This made Landeron a center of production for electronic movements in the 1970s as part of Ebauches Electronics, Ltd. but declining demand lead to the abrupt closure of the Landeron factory in 1983.

Landeron Chronograph Families

Charles Hahn introduced a number of widely-used chronograph movements between the 1930s and 1970s, but a few stand out:

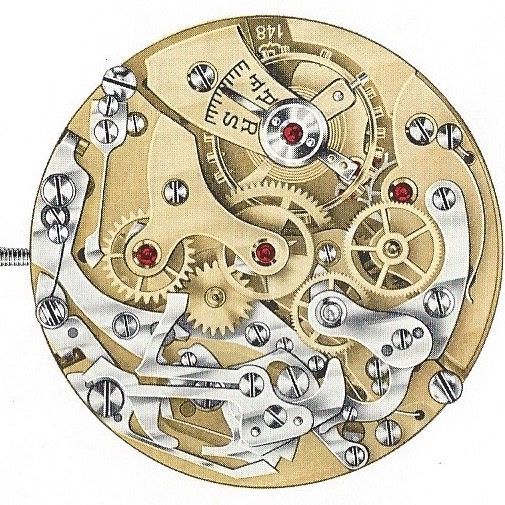

- Landeron Cal. 39 Column Wheel Movements – The 14.5 ligne Cal. 39 and Cal. 42 (with hour recorder) were widely-used modern movements in the pre-war period. Although not as fine as the famous Valjoux 23 and 72, Landeron’s use of the oscillating pinion technology made their movements among the most user friendly. After World War II, Landeron even introduced a cam-switching chronograph movement based on this design!

- Landeron Cal. 48 Cam Switching Movements – Charles Hahn and Marcel Dèpraz patented a cam-switching chronograph mechanism in 1939, with the pioneering Cal. 47 becoming the world-beating Cal. 48 in the 1940s. In all, over 3.5 million examples of this line were produced through 1970, including many with date, full calendar, and moon phase complications. There was even a column wheel version! Variants of Cal. 48 powered many classic chronograph watches, notably the Heuer Carrera Date, which used Cal. 189.

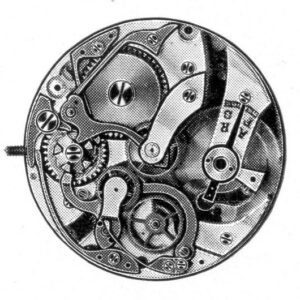

- Landeron Cal. 71 Cam Switching Movements – Although not as well remembered as the Cal. 48 line, Landeron also produced a larger 14 ligne cam switching chronograph. Cal. 71 is quite different from its predecessor but used a similar chronograph mechanism that also evolved over time. These are almost unknown today.

Before these high-volume lines were produced, Landeron also produced some smaller-volume movement families:

- Cal. 15 and Cal. 16 are monopusher chronograph movements produced in the 1930s

- Cal. 2, Cal. 3, and Cal. 9 appear to be related as well

- Cal. 10, Cal. 11, and Cal. 13 also share obvious similarities and all are 13 ligne column wheel movements

- Cal. 32 is the strangest of all Landeron movements, with no obvious relation to any other movement produced by the factory and the (unique?) placement of the column wheel above the stem

I have attempted to document all of these movements here in the Grail Watch Reference database. They are searchable by complication and function as well as using visual indications and specifications. This is added to my existing collection of historic movements from Universal, Valjoux, Venus, and more!

The Grail Watch Perspective: Discovering Landeron

I knew very little about Landeron prior to this research, and it has been an enjoyable process of discovery. The Landeron Cal. 48 family was truly groundbreaking, enabling the factory to thrive even as competing chronograph makers went bust in the “Chronograph Crash” of the 1950s, and the company powered many of the “quiet classics” of that period. Although cam-switching mechanisms are looked down upon today, they were an essential development to allow mechanical watchmaking to continue.

I welcome corrections, updates, and additions to the database. Contact me using the links provided at left!