This weekend I added a Zenith’s Elite family of movements to the site. These are an important series of modern automatic movements yet are not well-understood or documented. Introduced in 1994, the Elite series gave Zenith a compact movement that was robust, reliable, and could support complications across a wide range of watches. The series was almost retired in 2015 but has been given a new lease on life and is today one of two main movement lines from Zenith, along with the famous El Primero chronograph.

Jump right to the Zenith Elite family here on Grail Watch Reference or stick around for the back-story

Zenith’s Bread and Butter Movement

Mention Zenith to a watch enthusiast and they’ll likely start talking about the famous high-beat automatic chronograph known as El Primero. And for good reason: Not only is it historic, it’s also got a fun survival story and is a great movement to boot. But a company can’t rely on a single movement for all of its sales, especially a complex and expensive one.

In 1991, the Swiss watch industry was finding its way out of the quartz crisis, with complicated automatic movements leading the charge. IWC and ETA were showing what could be accomplished by layering a module on top of a reliable base, and every manufacturer was scrambling to secure such a movement. Zenith technical director Jean-Pierre Gerber lead a team to create a design of their own. It would be a relatively small and thin automatic movement with specifications similar to ETA’s leading Cal. 2892-2. The company was using computer-aided design (CAD) technology for the first time, and reportedly brought in help from consulting company Conseilray.

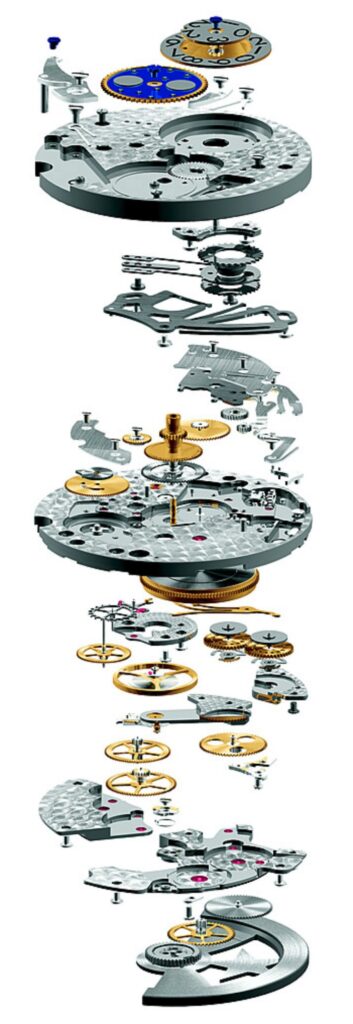

The resulting Zenith Elite movement would prove to be an excellent all-around performer. It was thoroughly up to date, with modern features including hacking seconds, instant date change, and a ball bearing rotor. The Glucydur balance ticked 28,800 times per hour but the design was efficient enough to run for over 50 hours from a single mainspring barrel. It measured just 11.5 ligne (25.60 mm) diameter and 3.28 mm thick, making it even slimmer than the similar ETA 2892.

At a time when subdial “small seconds” were seen as old-fashioned, Zenith designed this into Elite movement. Stranger still was the location of this subdial: 9:00 on the dial. Perhaps this was to add interest and a feeling of complexity to the watches that used the new Cal. 680, but it remains an odd choice. Zenith also offered a similar movement, Cal. 670, with central seconds, but this never seemed to be the focus. The small seconds movements were much more prominent in the Elite range, and far more varieties were produced.

Early variations on the Elite included the hand-winding Cal. 650, two-handed Cal. 661, and models with a fan-shaped power reserve indicator between 1 and 2 on the dial. A popular complication was a central 24 hour hand adjusted using a simple pushbutton at 10:00 on the case. These complications would appear in various combinations with date and moon phase for 25 years. Perhaps the most unusual member of the family is Cal. 689, which moves the small seconds subdial to the traditional location of 6:00 on the dial. This gave it a look entirely unlike the rest of the Elite series.

Early in the 2010s, Zenith recognized that the diminutive Elite movement wasn’t a good match for the ever-larger cases preferred by modern buyers. The company set about designing a new larger movement, likely intending to slot it above the Elite as a basis for future complicated models. The result was Cal. 6150, shown in late 2014 but officially launched in 2015. This double-barrel movement boasted 100 hours power reserve and a generous diameter of 30 mm, and Zenith’s new CEO Aldo Magada suggested it would see widespread use.

Outgoing CEO Jean-Frédéric Dufour had radically reduced the number of models offered by Zenith and directed the company to switch to cheaper Sellita SW300 movements for low-end models. This would have pushed the new Elite movement up-market at the expense of some of the hard-won respect the brand had earned from enthusiasts. But a funny thing happened over the next few years: Although a few models (notably the Pilot Type 20) did use Sellita movements, that plan was cancelled by the new CEO. In the mean time, the old Elite just soldiered on as the promised 6150 family never developed past that first movement.

As of 2020, Cal. 6150 no longer appears in the Zenith catalog. But five variations on the little #lite, including the original Calibres 670 and 680 remain in production! Indeed, when Zenith began experimenting with silicon escapement components in 2018, they turned to the original Elite Cal. 670 as a base. Today’s Elite Cal. 670 SK is found in the brand’s leading models, including the skeletonized Defy.

In 1994, Zenith’s model range was defined by two movements: The Elite and El Primero. That the same is true in 2020 is quite remarkable indeed!

Research Notes

I was able to catalog 23 different Elite movements based on the original 1994 design, and I believe that this list is comprehensive. It was surprising that there is no other such list on the internet, and I believe that this site might just be the most comprehensive resource for the Zenith Elite movement family anywhere!

It was extremely hard to locate solid information on these movements, and I rely primarily on two sources of information:

- Archived copies of the Zenith-Watches website dating from 2001 to present

- A trove of Zenith press releases from 2003 through 2008

- A full-line Zenith catalog from 2011

- Contemporary coverage in Europa Star, WatchTime, and QP Magazine

I did not use sources like WatchBase, Ranfft, or Caliber Corner at all, since I found their information quite lacking and often incorrect. The same is true of popular forums, where many posters are confused about which movement is which and what the specs are. I found this odd, since most online enthusiast communities have decent information about many brands, but perhaps Zenith devotees aren’t as focused on the movements as others.

In fact, it was this conflicting and confusing situation that drove me to research this movement family. I could not believe that there was no other resource, given the universal acclaim Zenith has received for the Elite family.

All specifications listed in the movement pages here at Grail Watch Reference are based on manufacturer information. This is especially important since some important elements are inconsistent across sources, including the thickness of the base movement (is it 3.28, 3.47, or 3.88 mm?) and jewel count (does Cal. 690 really have 37 jewels?) When in doubt I chose not to include a spec rather than to include something dubious.

It was also difficult to trace the timeline of these movements. I compiled a list of the first mention of each movement in a contemporary source or on the website as a start, also researching the first appearance of the watch which used it. Happily Zenith encodes the movement number in the watch reference number, making this task quite a lot easier. Still, it is possible that some of my dates are too “late” if I missed an earlier use. But overall they should be quite reliable.

I’ve seen two versions of what I presume is the 670SK in the Zenith Defy Classic skeleton. One where the escapement in the upper left is quite visible (these are the images that show up most frequently), and one where the escapement is considerably more hidden (these images are harder to come by, and certainly none from Zenith themselves). Have you found any info regarding this?

This is a very interesting suggestion, and one that I will look into!